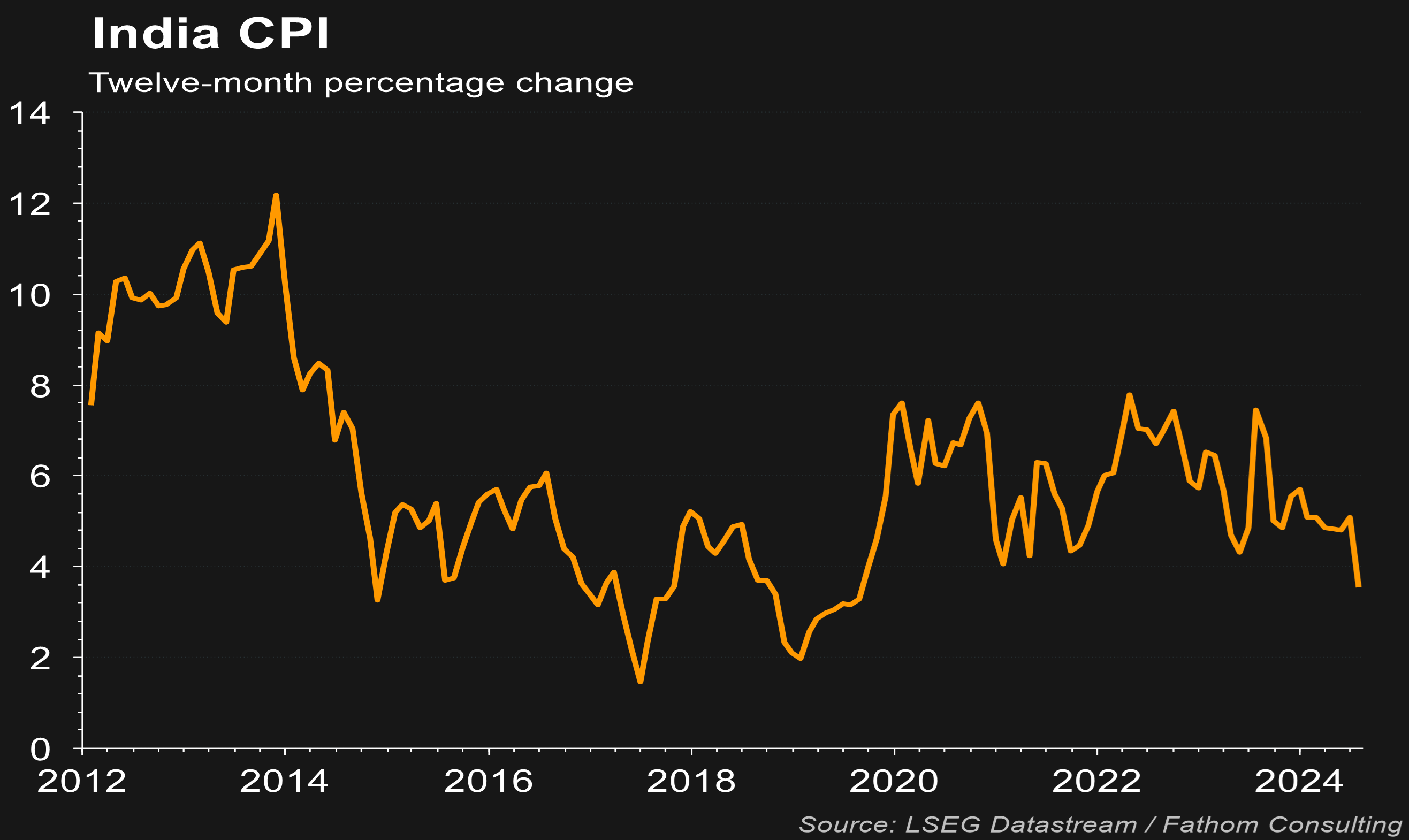

Indian assets have been strong performers but they still have further gains ahead. Structural economic and market reforms are ongoing, driving nominal GDP growth and EPS growth and encouraging market inflows. India is a model in how an emerging country can get richer during a period of de-globalization and under strong leadership.

The election, which gave PM Modi and the BJP ongoing power but without a majority, initially caused uncertainty. However, we agree with the consensus view that there will be ongoing political stability, and we believe that this should ensure continued growth.

The key question for investors to assess is whether the current growth is short-term and discounted, or the beginning of a multi-year process of sustained growth. The Mondrian view is that there are signs of the latter, driven by ongoing sensible government and central bank polices. A related question is whether India can achieve the growth rates that the East Asian countries achieved at their similar stages of development. Our view is that is unlikely, given India’s size, the more competitive environment for foreign direct investment, and India’s less reliance so far on the low-skill high-employing manufacturing sector.

Mr Modi aims for ‘viksit Bharat’ (developed country status) by 2047, with GDP per capita of $14,000. Goldman Sachs has estimated that the number of Indian people earning over $10,000 a year will grow from the current 60 million to 100 million by 2027. If achieved, these numbers would imply a huge increase in middle-class spending. However, to drive this process, the bottom end of the labour market needs to make faster progress. Within India’s working-age population of 1 billion, only around 100 million have formal jobs. The current state-run incentive scheme to promote manufacturing will only create 7 million jobs if it hits its targets.

The recent budget was encouraging in that it demonstrated that the government is intent on both expanding and accelerating this job creation process. The Chief Economic Adviser Nageswaran stated that India needs to create 8 million non-farm jobs annually until 2036.

The budget allocated $24 billion of new spending on job creation over the next five years. This spending includes new training programs for women, government contributions to employees’ first months wages, reimbursing some of employers’ social-security contributions, and a scheme to provide internships at the biggest Indian companies for 10 million young people.

The second focus of the budget was the agriculture sector, which employs 45% of India’s workforce. The budget committed to allocating $18 billion to the sector, with innovative plans to link farmers with digital land records and crop surveys, and to give farmers better access to information like market prices. In addition, the government is going to introduce high-yielding and climate-friendly crop varieties.

In addition to job creation, India needs to broaden its economic focus from mainly tech in Bangalore to other areas and there are some positive signals in this area. Tata Electronics is investing $3 billion in a chip plant in the remote state Assam, creating 27,000 jobs. Another remote state, Odisha, has recently opened Indian’s biggest vaccine plant. In addition, India might need to expand further beyond its tech sector so that it becomes the global hub for the digitalizing world and create some cluster export industries like defence and food.

Relations with China suffered significantly in 2020 after the deadly clash in the disputed Himalayan border area. However, there are signs that both sides are beginning to realize their need for the other. China has rising concerns relating to its own economic prospects as its property sector continues to languish and as trade barriers escalate globally. On the other hand, India, as it develops its industrial base, needs Chinese technology, investment and expertise which is particularly vital for India’s huge infrastructure plans. As an example, a state-run Chinese company has provided 250 high-tech cranes at new Indian ports.

It is encouraging that the 5 new “buffer zones” in 7 of the Himalayan hotspots have resulted in less border friction. There have also been other signs of reconciliation, like the relaxation of Indian visas for Chinese professionals in some industries, a visit from the Chinese ambassador after an 18 months hiatus, and also softening rhetoric from both sides. The process is slow and there are key areas in the relationship that still need to be addressed, like the outlawed Chinese apps and the tax and legal crackdown on Chinese mobile phone producers. Nevertheless, it would be a positive sign for investors in India if the softening trend continues.

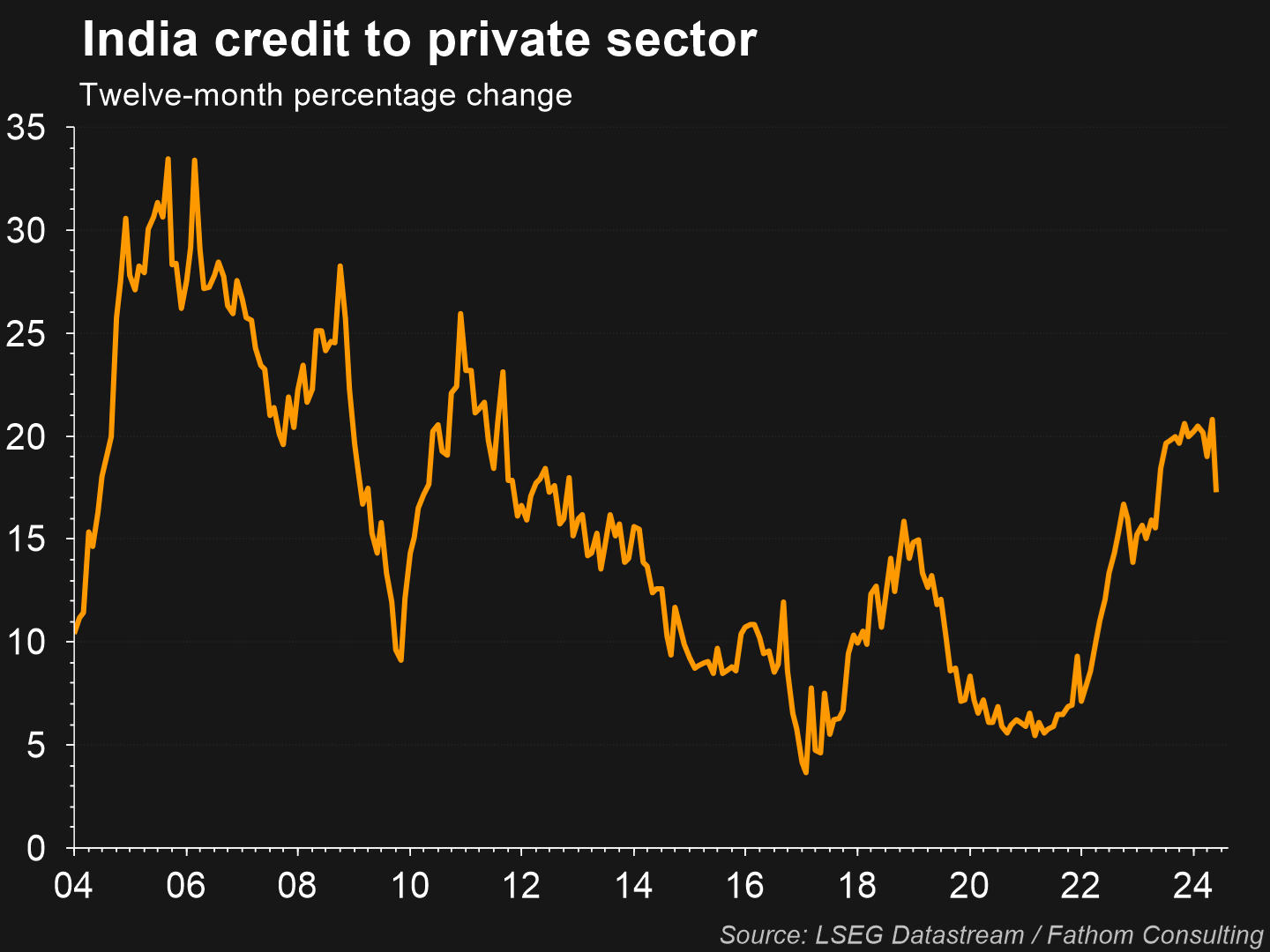

The average EPS growth over the last ten years has been 10%. This, along with the market re-rating, has taken the BSE Sensex Index to 25X forward earnings. The P/B is a high 2.5X. Small caps have generally outperformed over the last 30 years, and this has continued since 2020, and these small caps are more expensive than large caps.

Whilst on the surface this looks expensive, there are two off-setting factors – the first is that the strong EPS growth looks sustainable assuming sustained strong GDP growth, and secondly the market offers great opportunities on a selective basis. The preferred companies are those which are raising their returns on equity without leverage, and India has a high proportion of these within the index. Small and mid-caps also offer opportunities as many are operating in some of the newer growth areas and many more are very under-followed and under-owned. The Mondrian approach is to find fund managers who are on the ground stock pickers.

There is likely to be ongoing buying support from both local and foreign investors. The local retail equity culture is strong, with buoyant demand (Indian mutual equity funds have quadrupled to $330bn over the past four years, driven by higher incomes) and by buoyant supply (huge issuance of $28 billion so far this year, with IPO and secondary issuance strength). There are now 90 million retail accounts, up from 30 million accounts at the start of 2020. 20% of the population now own stocks. The local institutional base has increased too, and now holds 9% of the total market.

The market is now broad and liquid enough for large foreign institutions, with over 180 companies with market capitalizations of over USD 1bn. Many of these large caps are now held by Indian funds and by broader Asia funds.

JP Morgan has recently added India’s sovereign debt to its EM index, which should drive inflows. 28 Indian sovereign bonds worth USD 400 billion have been added, giving India a 10% share of the EM index. This reflects many years of negotiations between India’s government, banks and investors, which resulted in the country easing administrative controls and improved bond tradability. Credit ratings upgrades look inevitable and will accelerate issuance, inflows and also lower the cost of capital for local companies.

So far this year the 10-year sovereign bond has rallied by around 20 bp to 7%.

It is not too late to buy Indian assets. Despite the significant challenges ahead, the policy impetus is expected to drive continued growth. Investors need long-term horizons, risk appetites to withstand periodic consolidations, and access through local stock picking managers.